Chile is a land of amazing diversity. In the south, winds blast across the beautiful Patagonian mountains and glaciers, while cold antarctic waters stream into the thousands of fjords along the coast. As you move north, you are greeted by the Aysen region, a rain-soaked area of green loaded with lakes and rivers. Moving north of the Aysen region, you find yourself in the central valley of Chile, hemmed in by the Chilean coastal range on one side and the Andes on the other, this region has become famous for producing some of the world’s best wine. And finally, in the far north of Chile, you will find yourself in the driest place on earth, the Atacama desert.

It is here in the Atacama Desert where I witnessed landscapes utterly devoid of life for the first time. Kathy and I spent time in the Thar desert in India, but there was plenty of life there. The outback in Australia also had plenty of grasses and kangaroos bouncing about. However, here in the Atacama, there are vast stretches of land where not even cacti can survive. To give you a better idea about how dry the Atacama actually is, here are a few mind-bending statistics/facts:

- Average Rainfall per year across the Atacama Region: .6 inches/15mm

- Average Rainfall per year in the city of Arica: .04 inches/1mm

- Some weather stations in the Atacama have NEVER recorded rainfall

- Periods of up to 4 years have been registered with no rainfall in the central sector

- Evidence suggests that the Atacama didn’t have any significant rainfall between 1570-1971

- It is so arid that mountains higher than 6,000m/20,000ft are completely devoid of glaciers

The reason the Atacama is so dry is because it is situated between two mountain chains, the chilean coastal range to the west and the Andes range to the east. Both of these mountain ranges have sufficient height to prevent moisture from either the Atlantic or Pacific oceans from reaching the Atacama plateau in between. It’s effectively trapped in a two-sided rain shadow.

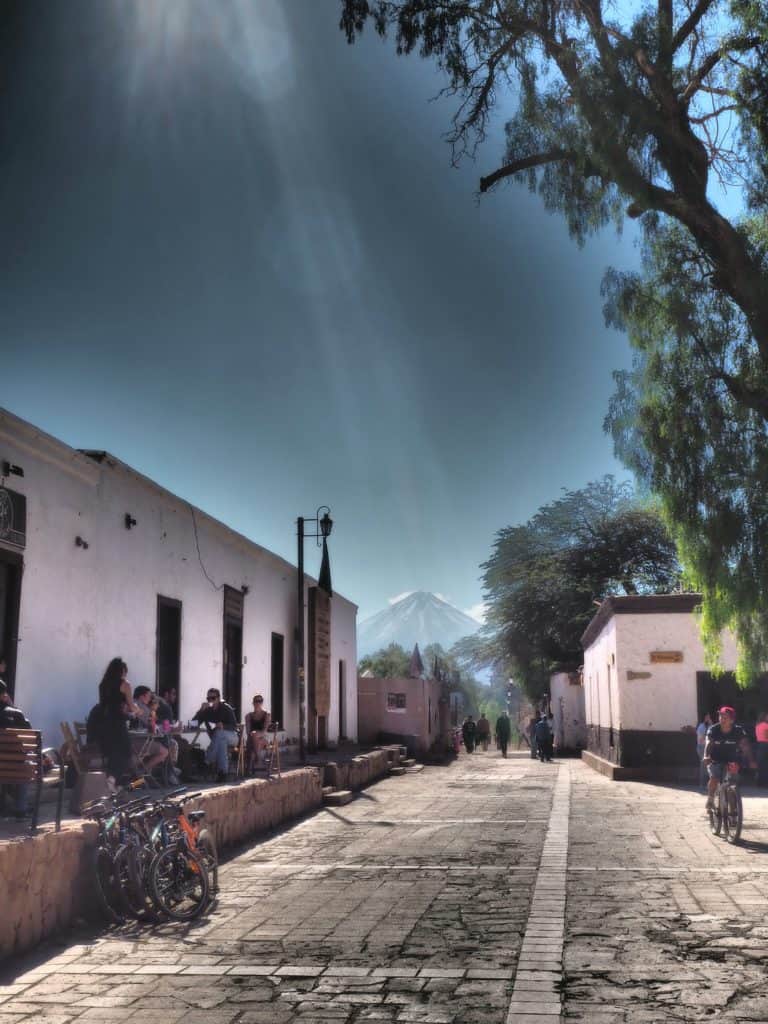

Nevertheless, there is beauty even in such a hostile place as this. The first two days in the Atacama I rented a bike and cycled through Valle de la Luna (Valley of the Moon) and Valle de la Muerta (Valley of Death). The landscapes were exactly what these two names imply; moon-like and devoid of life. That may sound boring, but it was a fantastic two days spent exploring the unique rock formations. Well, it wasn’t all great I guess, for the rocky roads left me with a sore butt after those two days 🙂

After spending a few days in the desert proper, I decided to check out the Chilean Altiplano (high plains). Technically the altiplano is not a part of the atacama desert, but it is close enough to be well worth the visit. At an elevation between 3,500-5000m (11,500-16,500ft) these high plains receive the majority of their moisture in the form of snow in the winter. The snows then melt in the spring, feeding streams which then drain into the region’s many lakes. These lakes are not normal lakes, however. Many of them are landlocked with no outlets, so the small amounts of salt brought in by streams becomes trapped as water evaporates which over time have left the lakes with a very high salt content. These unique lakes have become home to various extremophiles, bacteria and algae that can survive in the harsh saline environments (some lakes have a salt content as high as 37%!). This in turn has attracted those odd looking birds known as flamingoes.

The first salt lake I visited was lake Chaxa, which had two species of flamingoes feeding in it. The Andean flamingo feeds on micro-algea in the water, whereas the Chilean flamingo feeds on micro-crustaceans that live in the sediment. In order to get at these micro-crustaceans in the mud, the Chilean flamingo does a little dance, tapping its legs into the mud as it spins in a circle. It then filters its food from the sediments it’s kicked up in the process. Maybe this is where the “flamenco” dance originated from??Flamenco is spanish for Flamingo after all…

After laguna Chaxa I visited laguna Miscanti and laguna Miniques. These two lakes had far fewer flamingoes, but they made up for it by being surrounded by breathtaking mountains. The lakes are also situated at an elevation of 4,200m/13,775ft, so after just a few minutes of walking around I was out of breath. Not from the amazing views, but rather from the lack of oxygen at such high altitude. I finished out the day at the aguas calientes salt flat, a large expanse of salt surrounded by brown mountains.

On my last day in the Atacama I took a trip up to the Salar de Tara (Tara salt flat). The Tara salt flat is actually a large salt lake that is surrounded by dry plains, which in turn is surrounded by mountains. The area seems to be devoid of life until you get close to the lake, at which point grasses and shrubs begin to grow because of the small streams that drain into the lake. Vicunas (wild predecessor of the alpaca) graze on these grasses as do the viscachas (rabbit- like rodent) and Tuco-Tucos (burrowing rodent). In the lake, several species of birds feed along the shoreline, most notably flamingoes. They’re rather hard to miss, standing on those stilt-like legs with their heads stuffed underwater. Salar de Tara was a great way to end my trip in the Atacama. It was a beautiful thriving ecosystem stuck right next to the driest place on earth. It actually reminded me of Chile in general; an alluring land full of diversity and extremes.